Part One: Sending Spin

Recent Twitter activity by Lambeth councillors brought home just how important spin is to muddying the facts of the debate around Cressingham and the other estates netted by the council’s “Estate Regeneration Programme”.

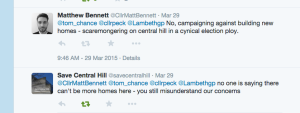

Lambeth council leader Cllr Lib Peck initiated a Twitter spat on Sunday, by accusing local members of the Green Party of “hypocrisy” over their local campaigning on housing. Peck’s righthand man in housing Cllr Matthew Bennett waded in, calling the Green Party’s support on Central Hill Estate in Upper Norwood, a “cynical election ploy”.

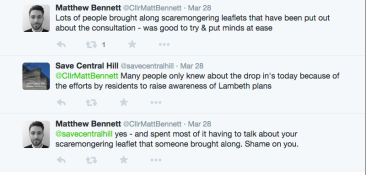

Continuing on his own Twitter warpath, Bennett even started chastising residents from the Save Central Hill group for “scaremongering”, and barked things like: “Shame on you” at them over the internet. He was upset because they’d distributed a leaflet which warned others living on the estate what regeneration can mean.

The points he steamed about had to do with the group’s mention of high density building to maximise profits, reference to other estates that have lost council homes through regeneration, and homeowners losing their homes. There were residents who, until they read the leaflet, weren’t even aware there was a consultation event, let alone one in which a demolition outcome was implicated. From the group’s point of view, these are all key risks that need considering by those affected. Bennett aggressively belittled those concerns, accused the group of of terrifying people he’d got to know, and lamented the time he’d had to spend assuaging their fears. Save Central Hill probably felt quite chastened by the public telling off.

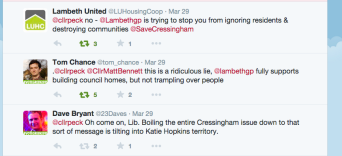

Peck’s tweet that sparked the whole row, missed the point entirely, but a host of observers spotted what she was up to. Tom Chance, who has ambitions to be a Green MP in a neighbouring constituency of Lewisham West and Penge, was quick to point out that it is not the new homes that are the problem, but the way the council is going about enforcing them:

The Green candidate was treated with the contempt you’d expect from a political opponent feeling threatened, but Bennett ignores the fact that Chance has worked extensively on housing and regeneration in his role as head of office for the Green Party at the Greater London Authority. As Chance explained in a subsequent open letter to Bennett, when there’s a lack of access to information, people like him step “into the vacuum”. Why wouldn’t Bennett want people to know the facts behind his spin?

One of the previous occasions when Bennett wasn’t interested in such things, was last summer, when London Assembly member Darren Johnson visited Cressingham Gardens. Following the visit Johnson, the leader of the London Assembly Greens and chair of the housing committee, then wrote to Bennett, suggesting he “provide support, advice and guidance as well as resources to properly investigate all of the regeneration and renewal options”, including the funding available for re-opening the six empty properties on Crosby Walk. Of course the advice was largely ignored.

To date, there have been more than 90 tweeted contributions to Peck’s thread. Far from showing up the Save Central Hill group and their network, what the councillors’ comments actually reveal is their blinkered assuredness that they are right. They keep repeating that this is all about solving the housing crisis and working with residents, but then they seek to smear anyone who, following direct experience, arrives at a critical view of their methods and motivations.

On the ground, Bennett et al’s behaviour suggests that for them, regeneration is about making a decision in advance, and then selling it to the people they are consulting via a series of PR initiatives. It’s this approach that’s letting Lambeth down on its Estate Regeneration Programme. The “co-operative council” slogan appears to most non-Labour observers as a pitch without substance, something you have to co-operate with rather than the other way round. (Brixton Buzz’s Jason Cobb talks about the co-operative council rhetoric in this story.)

Lambeth’s campaign, similar to the principles underpinning advertising, appears to assume that the people are ripe for fooling, or being sold something that they really don’t want or need. If that’s not their thinking, then they need to be very careful not to give that impression. They could do this by being clear and open when they answer questions from residents. They could keep their promises. They could even stray from the script.

Chance is actually doing the council a favour by writing his open letter. He invites Bennett to read the “Strategic Delivery Approach”, Lambeth’s original 2012 regeneration document.

It sets out the aims of the co-operative council on regeneration, which would remind Bennett of the “model of best practice”, that rightly recognises: “It is imperative that the Council develops this programme with the residents and that they own the objectives of the programme.”

Bennett might also gain some insights from the London Assembly report on best regeneration practice that Chance recommends he reads. Cressingham residents also gave evidence to the inquiry. The panel was concerned that Cressingham residents had to resort to more than 60 freedom of information requests to get basic information. The number of requests is now closer to 90.

Chance also flags the “highly unsatisfactory” selection criteria for estates being put into regeneration, which in both his and our view, were “based on subjective and misleading judgements about estates”. He clarifies that he in principle supports adding more homes on council estates, but that this needs to be done appropriately and by agreement.

On Cressingham, while the council has spent a lot of time and money on consultation, it has not been meaningful or constructive: Residents certainly have not owned the objectives. Back in December 2012, residents felt reasonably optimistic about the process after agreeing a five-stage process with the council, beginning with Stage One: “Common Understanding”. This was designed to establish what the issues were that the council was trying to solve through regeneration, and create a baseline of facts. This was to involve an estate-wide survey so that the claimed defects could be assessed and costed. The Common Understanding, logically, would involve analysis of how Cressingham was chosen for regeneration, and what the perceived benefits would be, and to whom. The idea was that once residents had a baseline understanding, the consultation could move to Stage Two, Three and so on, with enough time provided for community discussion and consideration at each stage. This would involve residents feeding back about how to improve the estate, and drawing up the terms for achieving improvements for the greatest benefit.

On all these counts, the Common Understanding failed. More than two years on, residents have barely got their teeth into to Stage Two. Find out about the failed regeneration criteria in the second part of this three-part series.

Who ever you are, you’re a very good writer.

LikeLike

Your clock is on GMT

LikeLike